4.6/51670+ reviews

4.6/51670+ reviewsFor any business that sells products, inventory is its lifeblood. But what happens when that inventory can no longer be sold at its normal price? Whether it's food that has spoiled, electronics that have become obsolete, or apparel that has gone out of season, this loss in value must be accounted for correctly for tax purposes.

The IRS has specific rules for handling spoiled or obsolete inventory. It's not a typical operating expense that you deduct on a single line. Instead, it's an adjustment made within the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) calculation. This guide will explain how to properly account for these losses to ensure your financial records are accurate and compliant.

Losses from inventory spoilage or obsolescence are not deducted as a separate line-item expense. Instead, the loss is reflected through an adjustment to your Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) on Schedule C (Form 1040), Part III.

The fundamental principle, outlined in IRS Publication 334, is that businesses must value their inventory at the beginning and end of each tax year. When inventory loses value, you account for this by reducing its valuation in your ending inventory. A lower ending inventory value results in a higher COGS, which in turn lowers your gross profit and, consequently, your taxable income.

To accurately account for spoiled or obsolete inventory, accountants and business owners must adhere to specific IRS guidelines for inventory valuation.

The IRS allows you to value inventory that is not sellable at normal prices due to damage, imperfections, or obsolescence at its expected selling price, minus the direct costs of selling it. This is often referred to as valuing inventory at the lower of cost or market value. By writing down the value of these subnormal goods in your ending inventory, you are recognizing the loss in the current year.

You cannot simply decide an item is obsolete and write it down. You must have objective evidence to support the new, lower valuation. This typically means you must actually offer the goods for sale at the lower price within 30 days of your inventory date.

If you donate inventory that you cannot sell, IRS Publication 334 provides a special rule for this situation. You can take a charitable contribution deduction, but you must also remove the cost of that inventory from your Cost of Goods Sold.

You do this by removing its cost from your opening inventory for the year (or from purchases if you bought and donated it in the same year). You cannot claim both a COGS deduction and a charitable deduction for the same inventory.

The tax deduction for spoiled inventory is realized by accurately calculating your Cost of Goods Sold.

The COGS formula on Schedule C is:

Beginning Inventory + Purchases - Ending Inventory = Cost of Goods Sold

When you write down the value of spoiled goods, your Ending Inventory value decreases. As the formula shows, subtracting a smaller number results in a higher COGS, which reduces your gross profit for the year.

Meticulous recordkeeping is essential to justify an inventory write-down. According to the IRS recordkeeping guidelines, you must maintain:

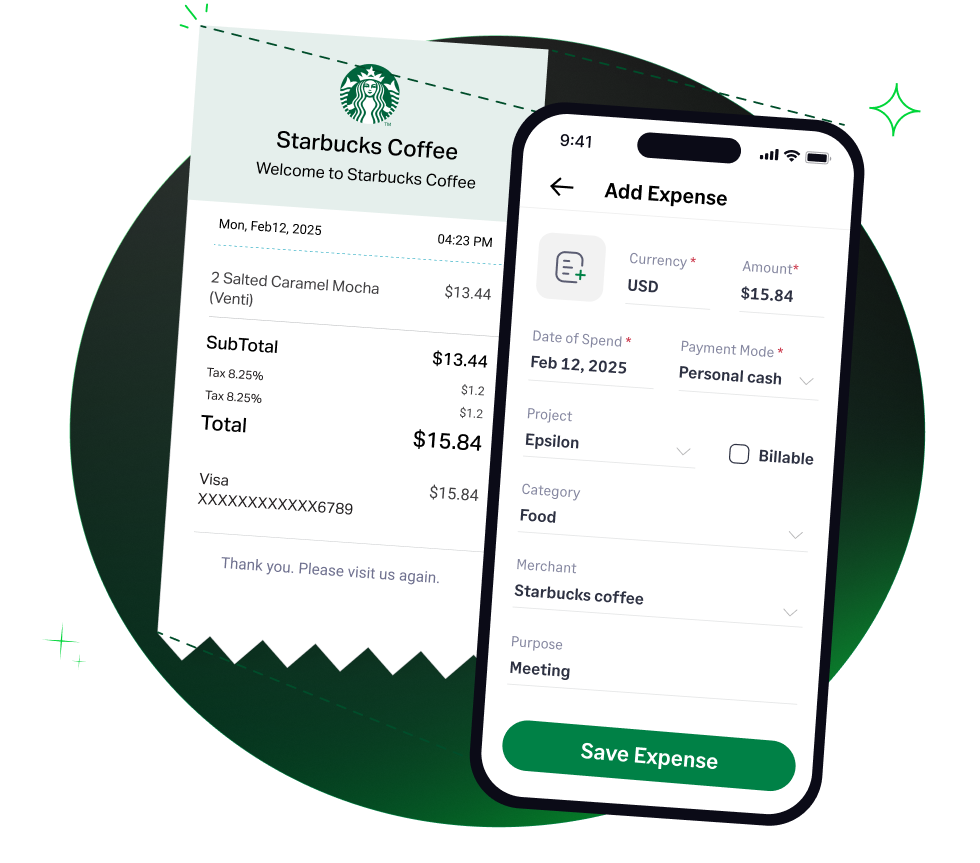

While Sage Expense Management is not an inventory management system, it is a crucial tool for capturing the initial costs and related documentation needed by your accountant to manage inventory valuation.