✨ Exciting news: Fyle is now part of the Sage family! Learn more in our press announcement >

4.6/51670+ reviews

4.6/51670+ reviewsWhen a business needs quick access to capital, a Merchant Cash Advance (MCA) can seem like an attractive option. A merchant Cash Advance fee provides a lump-sum payment in exchange for a percentage of your future sales. However, the unique structure of a Merchant Cash Advance Fees—and the high costs often associated with it—can create confusion for accountants and business owners at tax time.

The IRS does not explicitly define the tax treatment of Merchant Cash Advance Fees in its primary publications. The correct approach depends on whether the transaction is treated as a loan or a sale of future receivables. This guide explains the fundamental IRS principles that apply to these costs, helping you categorize them for tax compliance.

The fees associated with a Merchant Cash Advance do not have a dedicated expense category from the IRS. Their classification depends on the substance of the transaction. While some providers market Merchant Cash Advance Fees as a sale of future receivables, the IRS often examines the economic reality of the arrangement.

If the arrangement functions like a loan, then the cost of the advance would be treated as Interest Expense. IRS Publication 535 defines interest as an amount charged for the use of money you borrowed for business activities. Since the fee paid to a Merchant Cash Advance provider is fundamentally a charge for the use of their money, treating it as interest is often the most appropriate accounting approach.

The key to handling Merchant Cash Advance Fees costs is understanding the principles the IRS uses to evaluate financial transactions.

The most critical question is whether the Merchant Cash Advance Fees is a loan or a sale. The IRS has the authority to recharacterize a transaction based on its economic substance, regardless of the name given to the agreement. While the provided IRS documents do not specifically discuss Merchant Cash Advance Fees, they do provide the framework for what constitutes a true loan.

According to IRS Publication 535, for an amount to be deductible as interest, a true debtor-creditor relationship must exist between the parties. This means both you and the lender must intend for the debt to be repaid.

If your Merchant Cash Advance Fees agreement has characteristics that make it function like a loan (such as a fixed repayment amount, even if the timing varies), it is likely that the IRS would view the associated costs as interest.

It is also important to distinguish between the cost of the funds and any upfront fees that may be associated with them. IRS Publication 535 notes that certain expenses you pay to obtain a mortgage or loan, such as commissions or fees, may need to be capitalized and amortized over the life of the loan rather than being deducted immediately. Any separate origination or administrative fees for a Merchant Cash Advance could potentially fall under this rule.

The tax treatment of your Merchant Cash Advance Fees costs will follow from its classification.

If the Merchant Cash Advance Fees are treated as a loan, the associated costs (the factor rate or fee) are deductible as interest.

Because the tax treatment can be complex, meticulous recordkeeping is essential. You must keep:

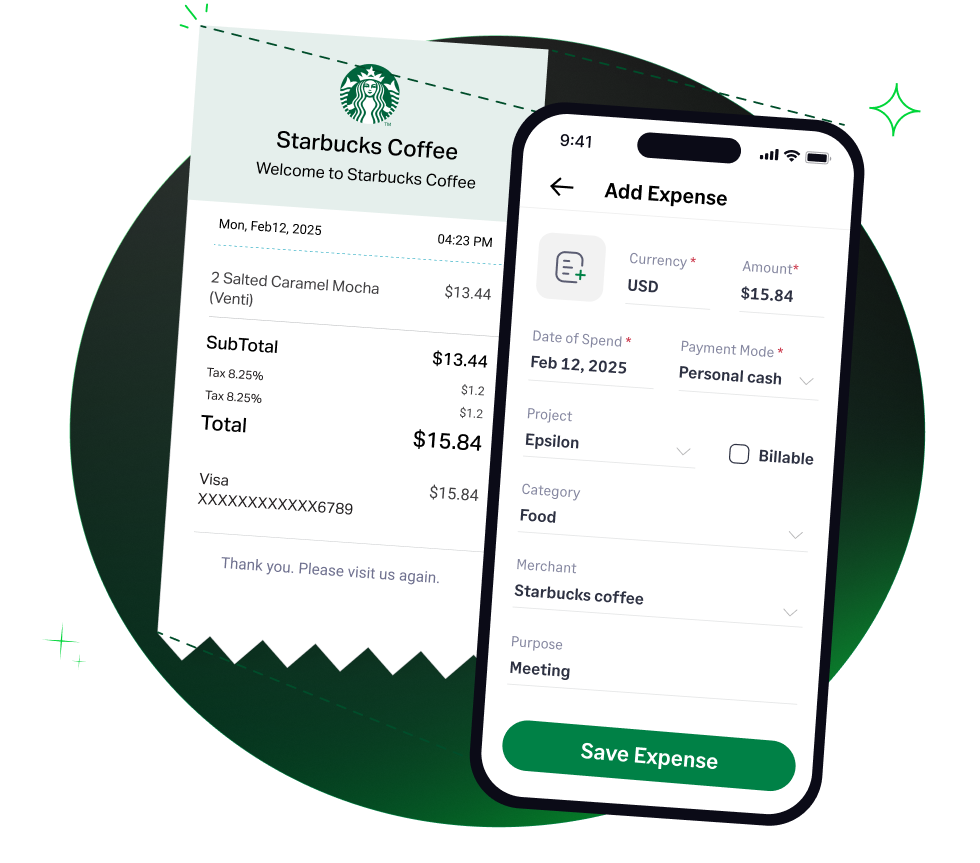

Fyle can help you track the complex flow of funds from a Merchant Cash Advance fee, providing a clear record for your accountant to determine the proper tax treatment.